‘It’s modern slavery’

‘It’s modern slavery’

New York’s dairy industry depends on immigrant labor, who find themselves under siege and in an increasingly difficult situation as a result of the federal immigration crackdown. Advocates say passage of the New York for All Act would help.

Editor’s Note: Workers interviewed for this story are identified by their last names only. The workers asked for this consideration as full identification would put them at risk of arrest or deportation.

Jiménez wakes up at 5:20 a.m., brews a cup of coffee and heads to the barn. An hour later, he’s checking calves born overnight, noting their sex and whether they’ve had colostrum, the nutrient-rich milk released immediately after birth. He prepares the milk, tests its temperature and hauls it to tanks before feeding the newborns. He works 12 to 14 hours a day, seven days a week.

Jiménez, 41, has worked in New York’s dairy industry for 21 years. He came from Oaxaca, Mexico, to pursue a degree in finance, but ended up on a different path.

“The idea was to come and make money for that, but I liked the money and stayed,” he said.

Like Saldaña, another dairy worker, Jiménez lives under the constant fear of deportation.

“Our community no longer feels safe with everything that is happening,” said Saldaña, 32, originally from Veracruz, Mexico. “We can’t even go to the store or church anymore. We are living in a difficult situation, and sometimes it crosses our minds to go back to our country.”

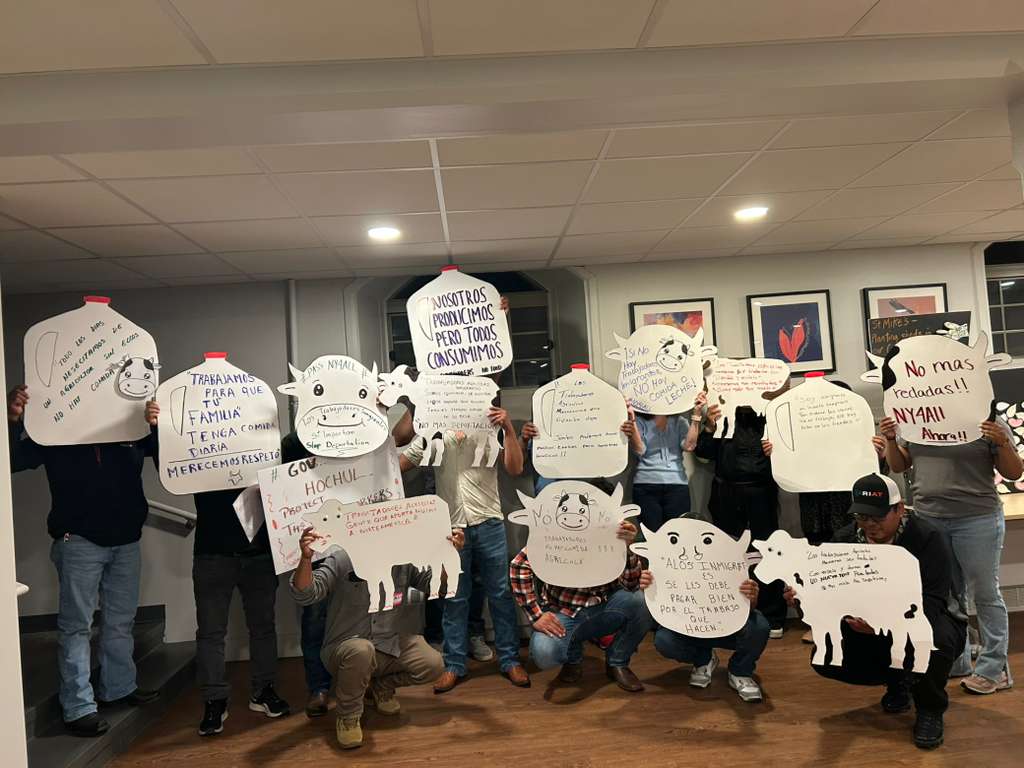

That fear drives Alianza Agrícola, a farmworker-led organization, to push for the New York for All Act, legislation that would prohibit local police from collaborating with immigration authorities.

The act calls for five key changes: public support for comprehensive immigration reform that does not expand guest-worker visa programs in ways that bind dairy workers to employers; employer safety plans, including private areas on farms where workers can go during raids; training for members on immigrant rights, such as understanding the difference between judicial and administrative warrants and the endorsement of the New York for All Act, which would bar collusion between local law enforcement and ICE.

New York’s dairy industry is one of the largest in the nation. The state has more than 3,000 dairy farms and ranks among the top five in the country, leading in yogurt, sour cream and cottage cheese. A 2024 national study estimated that nearly 90% of dairy workers in the U.S. are undocumented. These workers keep the state’s dairy sector running, despite the growing uncertainty as immigration crackdowns and labor insecurity continue to shape their daily lives.

Mina Aguilar, director of advocacy and campaigns at the Workers’ Center of Central New York, said the approval of the New York for All Act is urgent.

“We had conversations with the Farm Bureau and they kind of pushed our concern to the side,” Aguilar said.

Both the Workers’ Center of Central New York and Alianza Agrícola pressure the New York Farm Bureau, the state’s most influential agricultural lobbying group, to support immigrant workers.

“They are supposed to be representing farmers; they’re supposed to be representing workers,” Aguilar said. “It’s impossible to defend workers and act as if you support them if you don’t acknowledge immigration status.”

The organizations have opened a petition to collect signatures and plan to submit it in December to the New York State Farm Bureau during their annual meeting with all the bureau’s members to decide their policies for the following year. They have more than 500 signatures so far.

This is not their first attempt. On June 9, Alianza Agrícola and the Workers’ Center of Central New York sent a letter to the Farm Bureau demanding the promotion of agriculture and worker education. The bureau declined support.

Alianza Agrícola said that for the bureau, the solution relies on extending the H2A visa to include dairy workers and not only farmworkers, but this organization and Workers’ Center of Central New York reject that.

“Expanding the visa program to include dairy workers would just tie workers to their employers because we know that the visa program itself right now is a very flawed system and there’s lots of labor violations that happen,” Aguilar said

H2A is a temporary visa. Dairy work runs year-round, and visa holders must work for one farmowner, unable to negotiate wages, benefits or safer conditions.

“It’s modern slavery; that’s what we call it,” said Jiménez.

For Saldaña, who arrived almost 13 years ago, those protections are essential.

“This administration has been aggressive,” he said. “We all know this country has been built by foreign labor, by the cheapest labor, and it feels unfair. We’ve given so much to the industries we work in: our youth, our effort.”

Jiménez has seen the dairy industry change, but said inequality persists. A 2019 state law gave farmworkers the right to one day of rest each week and three sick days per year. Still, he said, disparities are clear:

“Americans take holidays off and nobody works, while immigrants keep working at the farm. That’s still not fair,” he said.

The Farm Bureau’s refusal to support immigrant rights legislation sends a painful message, Jiménez added.

“For us, their lack of support makes it clear that we’re disposable, easily replaceable, and that racism and discrimination against us continues just like from the president,” Jiménez said. “They just use us to do the work, but they don’t care about our suffering. For them, the economic side is more important than the human being.”

The Farm Bureau declined to comment for this story, as did Jeremy Cooney and Zellnor Myrie state lawmakers, making it unclear why the legislation, which is still pending, has not been advanced to a vote.

Despite that, the workers and their advocates vow to keep speaking out, saying they know the value of their work.

“Without us,” Jiménez said, “there is no dairy industry.”