Exposing the past: How illegal police searches fuel racial discrimination

How illegal police searches fuel racial discrimination

Questionable and illegal police searches resulted in limited discipline for many officers in New York, as the tactic fueled racial discrimination.

A joint investigation between the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Central Current and USA TODAY Network-New York.

Police in New York faced limited discipline for conducting questionable and illegal searches that fueled racial discrimination and excessive force within law enforcement over the past two decades, new records and data analysis revealed.

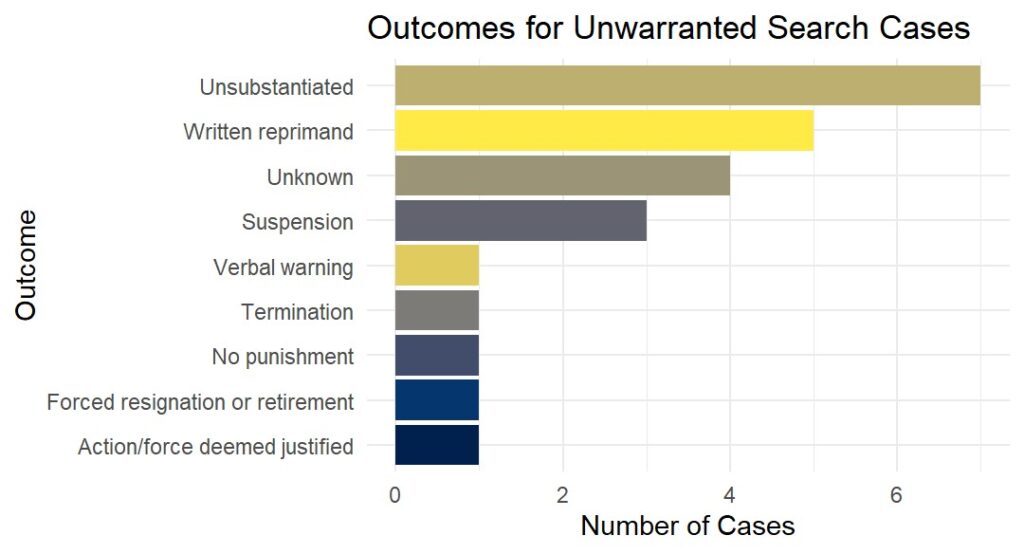

Strikingly, nearly one-third of the 24 unwarranted search misconduct cases reviewed for this article involved complaints of police using excessive force, underscoring how everyday law enforcement interactions escalated into dangerous situations for both officers and civilians.

Examples of blatant violations of rights spanned from a cop digging through young boys’ Halloween trick-or-treat bags in a close-knit Finger Lakes village to a broad mix of unjustified police searches of people and their vehicles across the state, records show.

This kind of police misconduct — and the discipline that may or may not follow — is the focus of an ongoing USA Today Network investigative series in partnership with Syracuse University’s Newhouse School and Syracuse nonprofit newsroom Central Current.

Answers to questions about how officers in New York police departments are disciplined for misconduct were made available thanks to the repeal of section 50-a of the state Civil Rights Law in June 2020. The repeal allowed access to police disciplinary files and records previously shielded from public view, which led to the creation of USA TODAY Network’s exclusive online database that lets the public search the documents as they get released.

‘Where the real danger lies’

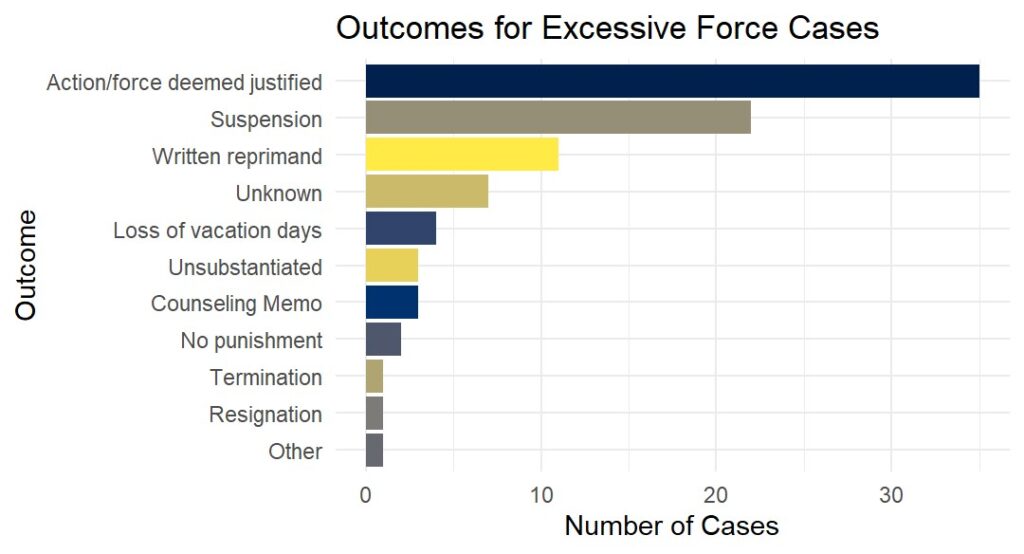

And when those misconduct cases escalate and result in police using force, officers also seldom faced serious discipline (As shown in the chart above).

Still, Steven Wasserman, an adjunct associate professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said the law gives police a lot of reasons to justify asking questions of a civilian on the street or to make a traffic stop.

“It is not illegal to stop a car for some very minor, inconsequential infraction, even though you’re not really interested in enforcing that infraction,” he said. “But of course, it is illegal to practice racial discrimination, and that is where the real danger lies.”

Police searches of vehicles often begin with routine stops for small infractions, like tinted windows or a minor traffic issue. Similarly, many police searches on the street started with questions about someone being in a high-crime neighborhood, records show.

But these seemingly mundane law enforcement encounters can quickly turn into broader investigations, even when there is no strong evidence of a serious offense.

At the same time, while some of these stops seem legal on the surface, they raise questions about intent. And officers involved in questionable or illegal searches are rarely held accountable in a meaningful way, according to an exclusive analysis of police misconduct records and data. We found:

- Out of 24 misconduct cases reviewed for this article, about 30% (involving seven different officers) received toothless reprimands or no punishment at all.

- One third of the misconduct cases were deemed unsubstantiated or justified following internal investigations by the police, raising questions about conflicts of interest when police investigate their own.

- Suspensions without pay for officers found to have improperly searched subjects ranged from two days up to 15 days, with some departments using policies that lacked clear definitions for determining penalties. By contrast, suspensions for cases involving force were more severe, ranging up to 150 days.

In other words, officers were seemingly allowed to illegally search New Yorkers with impunity, although several misconduct cases resulted in arrest charges being abandoned.

What a court-ordered review of police searches found

A court-ordered review of New York City Police Department, or NYPD, discipline raised similar concerns. It found that Fourth Amendment violations, including improper searches and stops, often resulted in officers losing only a few vacation days, according to a report released last year.

The report also suggested these light punishments do not reflect the seriousness of the violation and can damage public trust in law enforcement.

Put differently, when a stop is based on a small excuse, it is often about something more, Wasserman said, before adding, “This is where bias can easily come in, whether intentional or not.”

At the same time, experts and legal advocates have asserted stronger oversight, clearer limits on pretextual stops, and more meaningful consequences for officers are needed to prevent unnecessary searches and protect civil rights.

Limited discipline for illegal police searches

Amid the push for reforms, cases of clearly illegal searches being conducted reinforced the negative impact on public trust in law enforcement.

One involved four young boys — ages 11 and 12 — who were trick-or-treating in the village of LeRoy, near Rochester, when they heard police sirens.

According to a misconduct report obtained from the LeRoy Police Department, Officer John Condidoria approached the boys and asked to search the bags of candy they were carrying.

Condidoria then frisked the boys and checked their bags for what he believed to be soap, eggs, or wax used in complaints of Halloween mischief nearby. After his search yielded no results, Condidoria drove away, and the boys went home. A father of one of the boys witnessed the events and reported Condidoria to his superiors for performing an unwarranted search on his son and the three other boys.

In New York, unwarranted searches are prohibited under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and Article I, Section 12 of the New York State Constitution. These protections guarantee citizens the right to be secure in their persons, homes, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Generally, police need a warrant based on probable cause to search; however, exceptions exist, such as when consent is given or evidence is in plain view. In the case of Officer Condidoria, there was no evidence of any wrongdoing by the boys he searched.

This case resulted in the officer being suspended for two days and required him to apologize to all the children whom he had improperly searched. Calls requesting comment from the police department and officer about the case did not receive an immediate response.

Meanwhile, punishment for illegal police searches was far from standardized from department to department, records show.

Captain Jeffrey Schmidt of the Cheektowaga Police Department, near Buffalo, described his agency’s use of a progressive discipline system, which raises the punishment level after each incident by an individual officer, not just because of circumstances of the wrongful action.

“If we’re seeing 10 days (suspension) here, 15 days there, 30 days here, it’s because they’ve become a disciplinary problem,” Schmidt said.

His comments came in response to USA TODAY Network questions about another unwarranted search, in which Cheektowaga Police Officer John Krauze was suspended for 15 days in 2008 after pulling over a car for a broken taillight.

Krauze then improperly searched the vehicle after placing the driver and passenger in his police car. A recent gun arrest showed up after the officer ran their names, which only gave him the ability to search near the driver’s seat, records show.

Police officers are not allowed to search a vehicle after removing its occupants, Schmidt said in a recent interview about the case.

After placing the occupants in his patrol car, Krauze searched the vehicle and found two bags of drugs underneath the driver’s seat. He claimed that these items were in plain view, which would have given him the authority to make an arrest. However, this differed from the accounts of other officers regarding the story.

According to an internal investigation, other officers stated that Krauze himself admitted the search was illegal, and there was no reason to bring this case to trial. The investigation also claimed Krauze did not state this when interviewed and refused to testify during court proceedings regarding the case.

The department ultimately suspended Krauze not only for the search but also for knowingly writing a false report and failing to perform his duty, records show. Krauze did not immediately respond to calls requesting comment.

Racial discrimination in police searches

The stakes of efforts to improve accountability for illegal police searches also captured national attention amid legal battles over NYPD’s “stop-and-frisk” policies.

Among the findings of New York City Liberties Union analysis of the policies:

- From 2003-2023, 90% of people stopped by the NYPD were people of color.

- Black and Latinx New Yorkers made up 52% and 31% of all stops despite being 23% and 29% of the population, respectively.

- White New Yorkers only made up 10% of stops though they represent 33% of the population.

- This means Black people were stopped at a rate nearly eight times greater than white people, and Latinx people were stopped at a rate four times greater.

Stop-and-frisk was a signature policy of the Michael Bloomberg mayoral administration in New York City, which spanned from 2002 to 2013. Over 96% of all stops that occurred from 2003-2023 took place during his time in office, the civil rights group noted.

Yet, while comparatively fewer stops occurred during the Bill de Blasio mayoral administration — nearly 135,000 — enormous racial disparities persisted every year of that era from 2014 to 2021.

Current New York City Mayor Eric Adams, a former NYPD officer, has also renewed debates over police stops and searches.

In 2022, the first year of the Adams administration, the NYPD made over 15,000 stops, the largest number of stops since 2015 (22,565 stops). This rising trend continued into 2023 where nearly 17,000 stops were made.

Still, the group added, “There is no evidence that ramping up stops makes New Yorkers safer. But we do know that many of these stops have been unlawful and that some have led to violent police misconduct.”

And in a sign of growing pushback against improper stops, New York City last year mandated that police officers track the race of people they stop for questioning, a move that could help curtail racial disparities in policing and spawn similar changes for departments nationwide.

About this project

This story is part of Good Cop Bad Cop, an investigative project from the USA Today Network, Central Current and Syracuse University. Over 30 reporting students from the Newhouse School dug into decades of New York police misconduct records to uncover policy and safety missteps among officers from Buffalo to Westchester County, and explain why these infractions matter to the public.